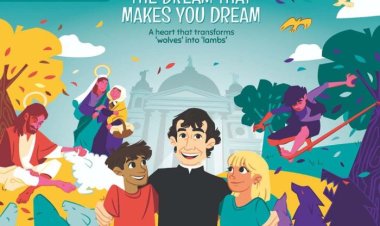

A Painting That Teaches the Nativity

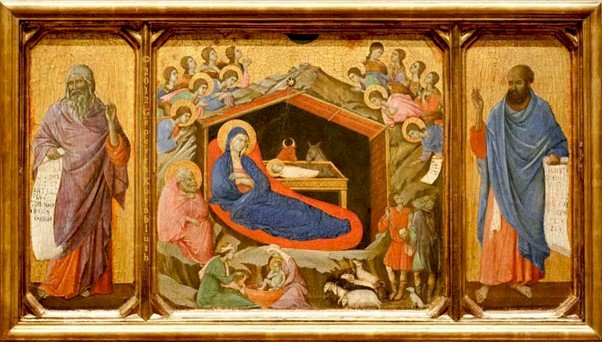

14th-century Nativity by Duccio di Buoninsegna, with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel.

A Painting That Teaches the Nativity - CNS - PUBLISHED DECEMBER 25, 2020

The “Maestà”, an 14th-century Nativity by Duccio di Buoninsegna, with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel. This altarpiece from Siena, Italy, tells the story of the Nativity in perfect visual terms.

Duccio was born in Siena between 1255–1260 and died there around 1318–19. One of the most important Italian painters of his time, he was active in Siena, but also created artworks in government and religious buildings around Italy. Completed by Duccio between 1308 and 1311, this panel was once part of one of the most important treasures of Western painting: the impressive Maestà altarpiece that visually dominated Siena’s cathedral for two centuries. It is now exhibited at the Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo in Siena.On completing the commission in 1311, Duccio became known for his fervent prayer to the mother of God, asking Mary to be the cause of peace for Siena.

‘Jesus was born in a humble stable, into a poor family. Simple shepherds were the first witnesses to this event. In this poverty heaven’s glory was made manifest. The Church never tires of singing the glory of this night.” These words from the Catechism of the Catholic Church (#525) focus our gaze on the mystery of that holy night when Advent preparations culminate in the great Christmas feast.

Inviting wonder in the face of the mystery of the Incarnation, Duccio’s painting, titled “The Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel”, is a stirring visual homily on the Christmas story. He sets the birth of Jesus within salvation history by framing the sacred moment with two prophets who announce the coming Messiah. The longings of Israel for salvation, echoed in our own Advent hopes, are now fulfilled perfectly in this time of grace.

For God extends definitively his hand of divine mercy by sending his own Son into the world.

In the Incarnation, human history finds its deepest meaning and destiny.

On the right stands the prophet Ezekiel with scroll in hand, foreshadowing the future birth of a saviour. On the left stands Isaiah, with his prophetic words also in hand: “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign; the young woman, pregnant and about to bear a son, shall name him Emmanuel” (Is 7:14).

At the centre of the composition is the virgin mother of God, with her newborn divine Son.

Her scale is twice that of any figure in the scene, highlighting her unique role in the divine plan of salvation. Mary is dressed in red and blue garments, colours that point to her Son’s divinity and humanity united in his divine person.

She gathers her blue robe around her while reclining on a red cushion as she looks with motherly love at her newborn Son, Jesus. Mary’s large scale and her recumbent pose evoke traditional icons of the Nativity.

Both mother and child are enclosed in a cave, an element drawn from Eastern iconography.

The only hospitality that the world offers is a bare, cold cave, warmed simply by the breath of animals who watch over them. One can feel the spiritual warmth of this holy scene despite the harsh coldness of its material poverty.

Below, Duccio includes two midwives who wash the infant Jesus, lending another ordinary human touch to this extraordinary heavenly moment.

Sitting close to Mary is St Joseph. To this saintly guardian of the Redeemer was given the singular blessing of being in closest proximity to the mystery of Christ’s birth. So Duccio places Joseph close to Mary, deep in wonder and awe as he ponders God’s marvellous work.

On the cave rooftop an exuberant host of angels gather around the virgin mother and child. Some angels raise their eyes to heaven with joyful melodies of praise to God. Other angels lean over the roof curiously, straining to catch a glimpse of the divine child. Still other angels announce to the simple shepherds the good news of salvation now at hand.

God’s desire for friendship with humanity is fulfilled perfectly in the birth of Jesus.

In the face of this greatest of divine gifts, the Incarnation, what is the most fitting human response?

Each of Duccio’s figures in his luminous Nativity scene radiates faith, hope and love in the presence of the newborn Jesus. God takes human flesh in his Son Jesus so that, in him, we might be clothed once again with the dignity of the children of God.

For this marvellous exchange made possible by the Incarnation of God our fitting response is to join the chorus of Duccio’s angels in a hymn of Christmas praise: “O come let us adore him, Christ the Lord!”. (Catholic News Service)